by: Zach Bethune, Thomas Cooley, Peter Rupert

The establishment data issued this morning by the BLS showed continued gains in the labor market with establishments reporting an increase in payrolls of 209,000 workers. While it is slightly lower than the last few months, with slower growth in the service sector (140,000), goods producing performed better than the last few months, increasing 58,000. The diffusion index, however, fell from 65.3 to 61.9, meaning slightly fewer firms reporting employment gains as compared to last month.

Average weekly hours has remained unchanged over the past three months, sitting at 34.5.

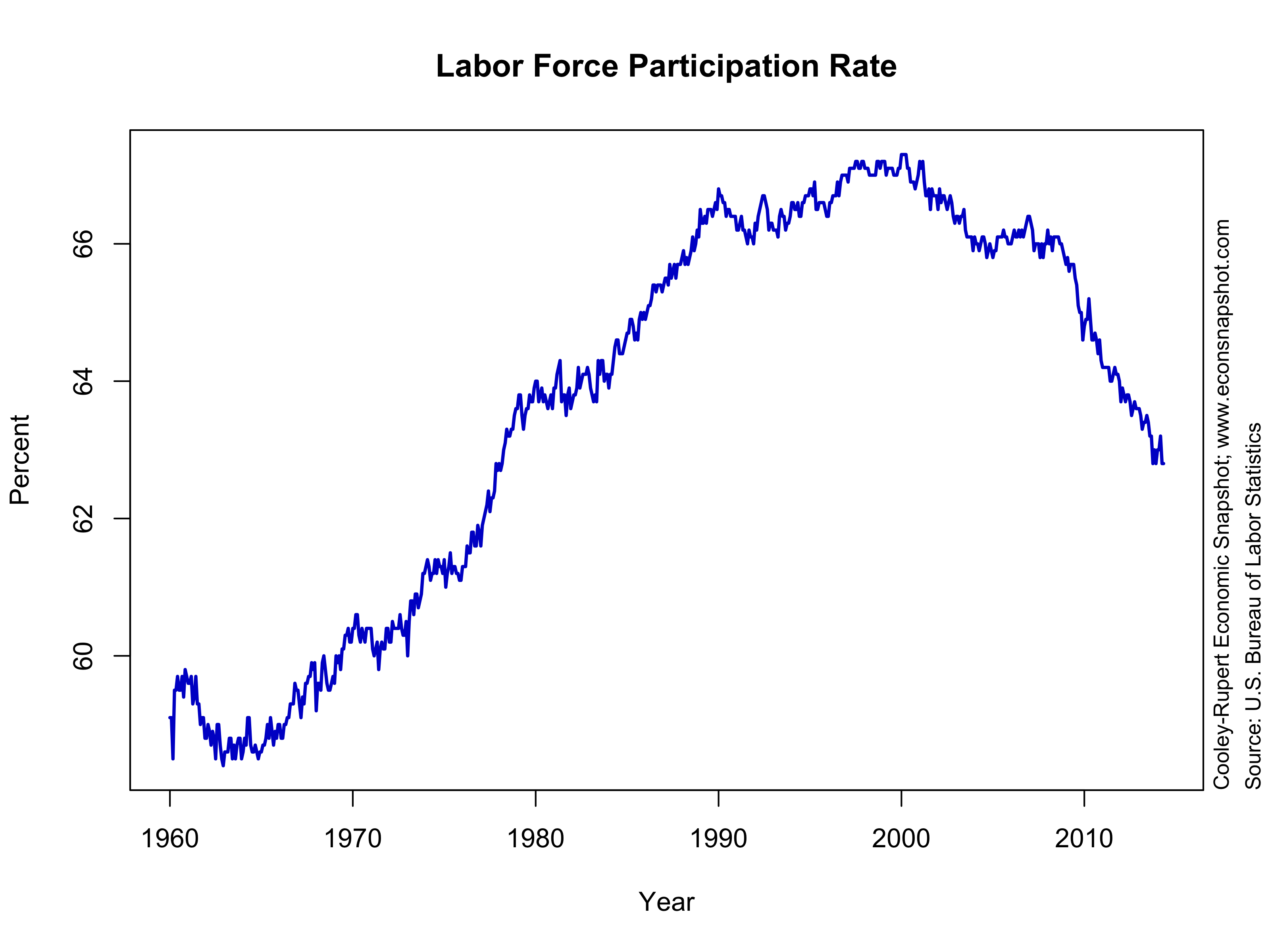

The household data revealed a slight increase in the unemployment rate, from 6.1% to 6.2%, with the number of unemployed persons rising 197,000 and the civilian labor force increasing by 329,000. So while the labor force expanded, the hiring did not keep pace, leading to an overall increase in the unemployment rate.

It is also worth noting that, even though employment is increasing, it is not creating upward pressure on wages. Average hourly earnings remained essentially stagnant the past month and have increased very little over the past year. This is an important reason why the Fed doesn’t see increased inflation pressure coming from the labor market.

Slack in the Labor Market: Who are the involuntary part-time workers and what are their outcomes?

A couple of weeks ago, the Federal Reserve submitted their semiannual Monetary Policy Report to congress in which they outline their current stance on the state of the economy and how that weighs on their decisions about monetary policy.

Following several months of positive reports on the labor market , tepid first quarter GDP growth and strong second quarter GDP growth, the central question for policy makers remains: Is ‘liftoff’ of the federal funds rate near?

The answer to that question in June was no. The answer in July is also no. The expectation appears to be to keep the target for the federal funds rate between 0 and 1/4 percent “for a considerable period after the asset purchase program ends”. You don’t have to read very far into the report to Congress or this week’s FOMC announcement to see why the Fed is so hesitant to move rates. From the first paragraph of the summary (emphasis added):

The overall condition of the labor market continued to improve during the first half of 2014. Gains in payroll employment picked up to an average monthly pace of about 230,000, and the unemployment rate fell to 6.1 percent in June, nearly 4 percentage points below its peak in 2009. Notwithstanding those improvements, a broad array of labor market indicators—such as labor force participation, hiring and quit rates, and the number of people working part time for economic reasons—generally suggests that significant slack remains in the labor market. Continued slow increases in most measures of labor compensation also corroborate the view that labor resources are not being fully utilized.

The July statement from the FOMC highlights the continued concern about labor market conditions (emphasis added):

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in June indicates that growth in economic activity rebounded in the second quarter. Labor market conditions improved, with the unemployment rate declining further. However, a range of labor market indicators suggests that there remains significant underutilization of labor resources.

The July statement adds:

The Committee currently anticipates that, even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below levels the Committee views as normal in the longer run.

While it is true that unemployment has come down substantially since 2009 and workers are finding jobs, they aren’t the kind of jobs you (or the FOMC) would expect from a healthy labor market. A large fraction of those finding work are those that find part-time jobs despite the fact that they would like to be working full-time, known as “involuntary part-time workers,” that is, employed part-time for economic reasons.

It is not uncommon in any state of the labor market to find a fraction of part-time workers to be involuntarily working part-time. Not all workers that want full-time work will get it–at least not right away; a part-time job may serve as a stepping stone to full-time work.

However, during the last recession the number of involuntary part-time workers more than doubled. There currently remains a historically high number of involuntary part-time workers. We use data from the CPS monthly survey to ask who composes this group, what types of jobs they hold, and how they transition out of part-time work.

Who are the involuntary part-time workers?

Below we compare the composition of involuntary part-time workers (jobs) across time. To do so, we use micro data from the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS) from 1997 to June 2014. For each month, we identify those workers that are currently working part-time and indicate that they would like to work full-time but cannot because of economic reasons. We ask how the pool of involuntary part-time workers has changed during the recession across 4 characteristics: sex, age, weekly hours, and weekly wages.

The figure above plots the percentage change in each variable (e.g., age) from its 2007 value for 2009 and 2014. Notice the first ‘bar’ of each variable is set at 0 to represent the values in 2007. We show each variable’s actual value next to the columns. Before the recession, the involuntary part-time workers were equally represented between men and women, were on average 39.8 years of age, worked about 22.5 hours a week, and made $7,570 a week.

At the depth of the recession, in 2009, the pool of involuntary part-time workers shifted towards men (the share of men increased to 53%) and older workers. Hours decreased slightly to 22.36. Average wages increased to $8,490 a week, potentially representing a shift in the types of part-time jobs.

Since 2009, the composition of involuntary part-time workers has mostly returned back to normal. The exception is the average age of these workers which remains elevated.

Do involuntary part-time workers eventually find full-time jobs?

The answer is, on average, yes. However, since the recession the incidence of finding a full-time job has fallen and remains low. The longitudinal aspect of the CPS survey allows us to follow households over a little more than a year. Below we plot the fraction of all workers who were working part-time for economic reasons a year ago, that reported working full-time in the current period. This represents the probability, or transition rate, of leaving part-time work and finding a full-time job.

In normal times this transition rate is around 0.45, meaning that 45% of all workers who work part-time but want a full-time job will find one over the year. During the recession, this rate plummeted to 0.35 and has stayed close to 0.38 since. It’s taking much longer for the labor market to clear these involuntary workers into full-time. (If we interpret these rates as Poisson, the average length of time it takes has increased from 2.2 years to around 2.8 years, or 1/.45 to 1/.35.)

Along other margins, the transition rates of involuntary part-time workers have returned to normal, which is good news. They aren’t going into unemployment as quickly as in 2009. While the rate jumped up during the recession it has since returned to around 0.06.

There is also no discernible trend of these workers dropping out of the labor force. The transition rate from part-time for economic reasons to out of the labor force has remained close to 0.1.

The considerable time it is taking for part-time workers to find a full time job is precisely the ‘slack’ the FOMC is thinking about when it is deciding to stay firm on monetary policy. While the unemployment rate has returned to more acceptable levels, there are many measures that continue to suggest the labor market is not ‘healthy’ and keeps the FOMC on the fence.