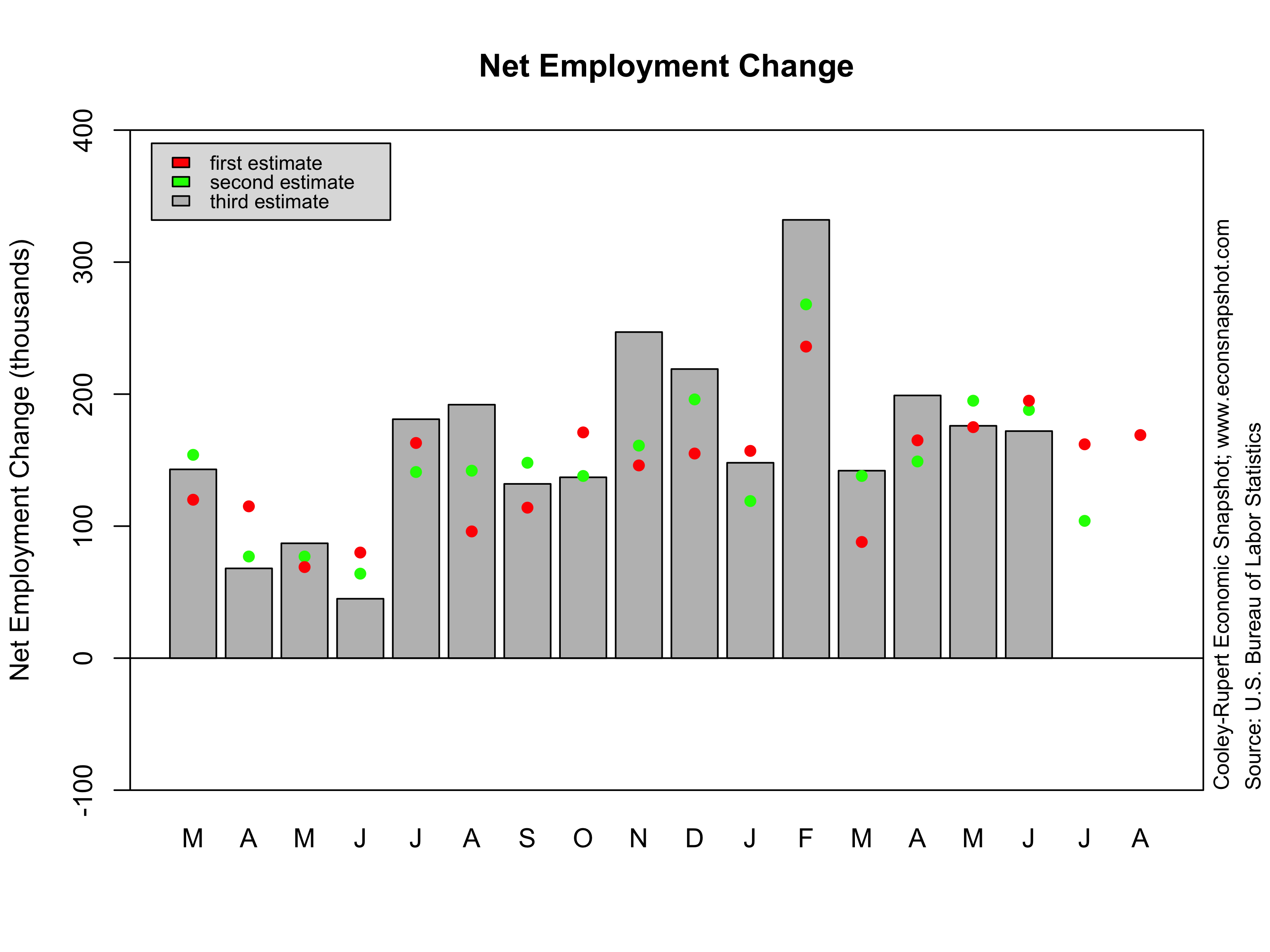

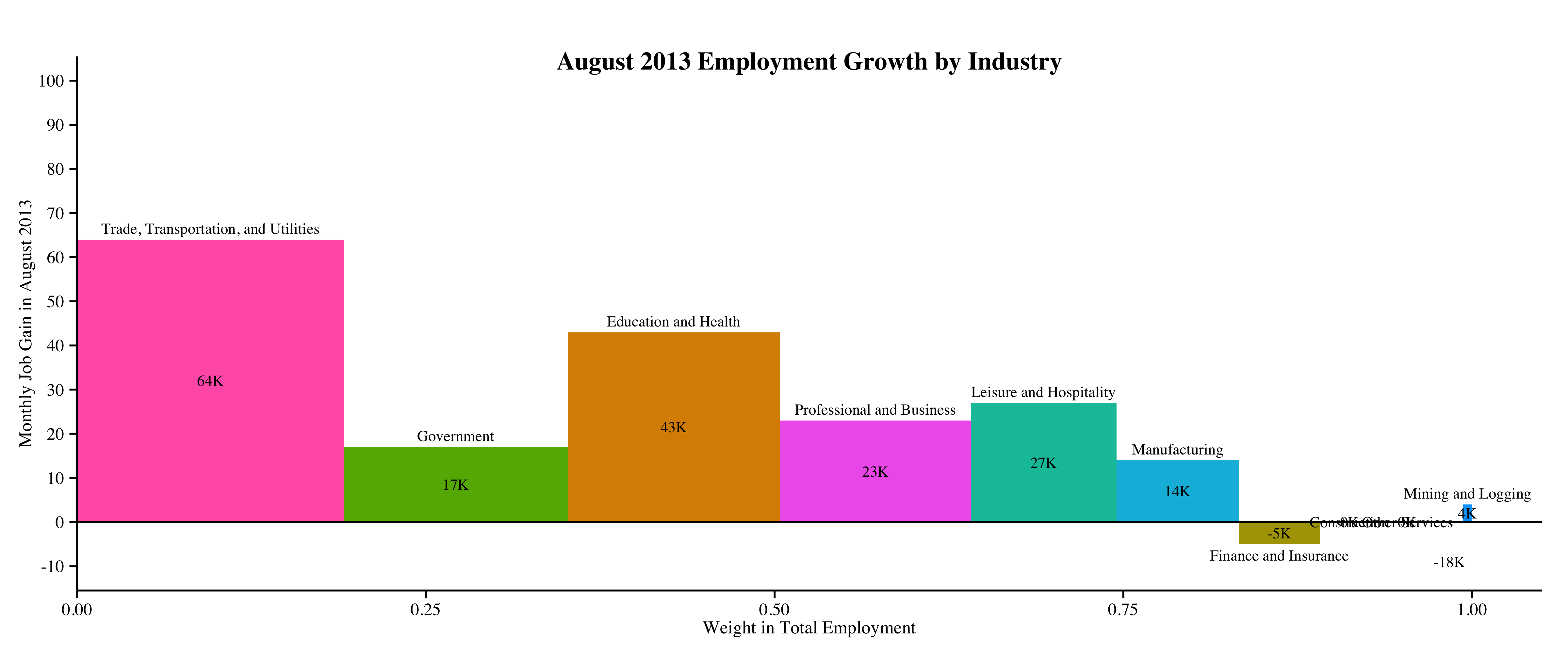

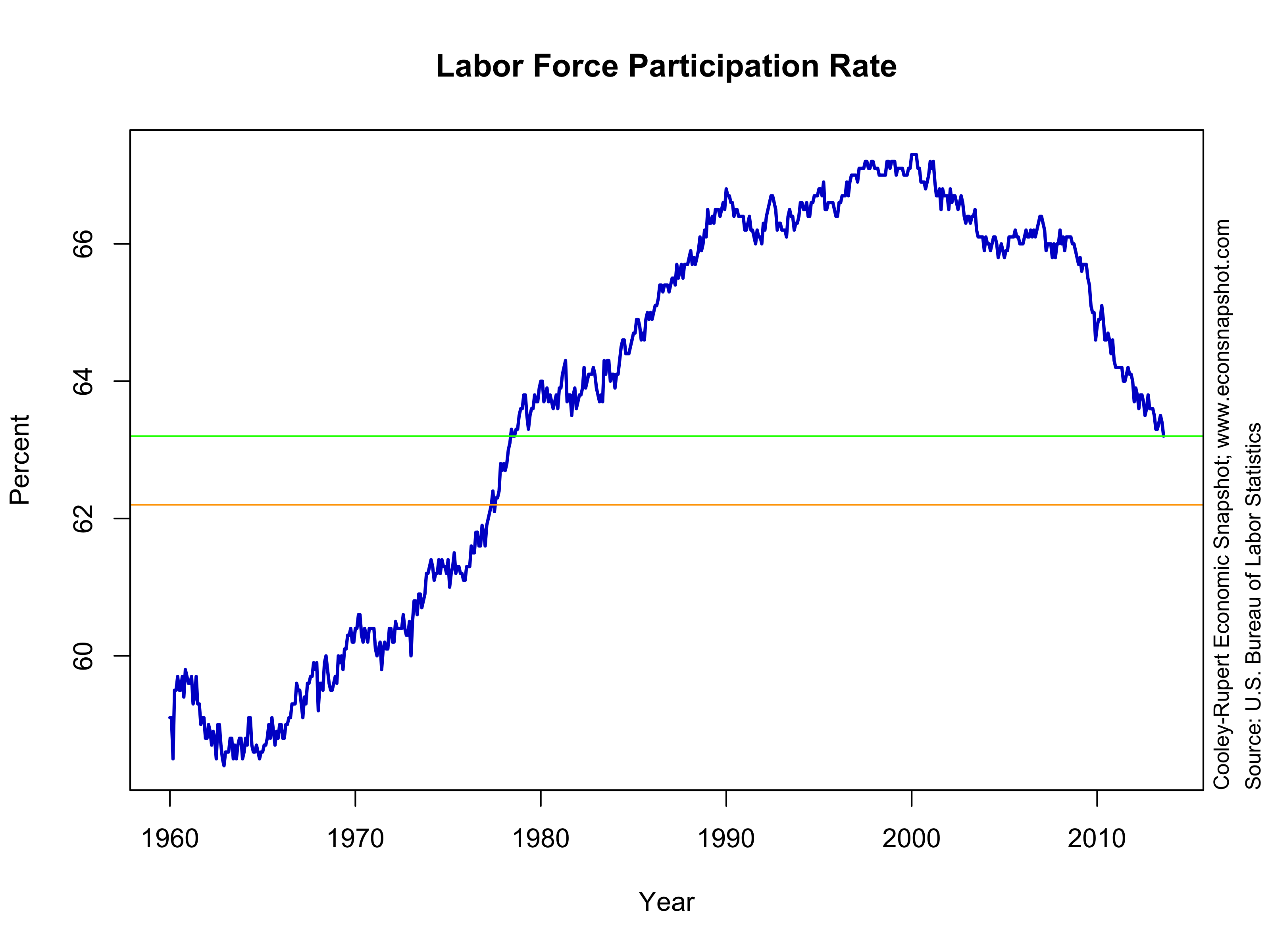

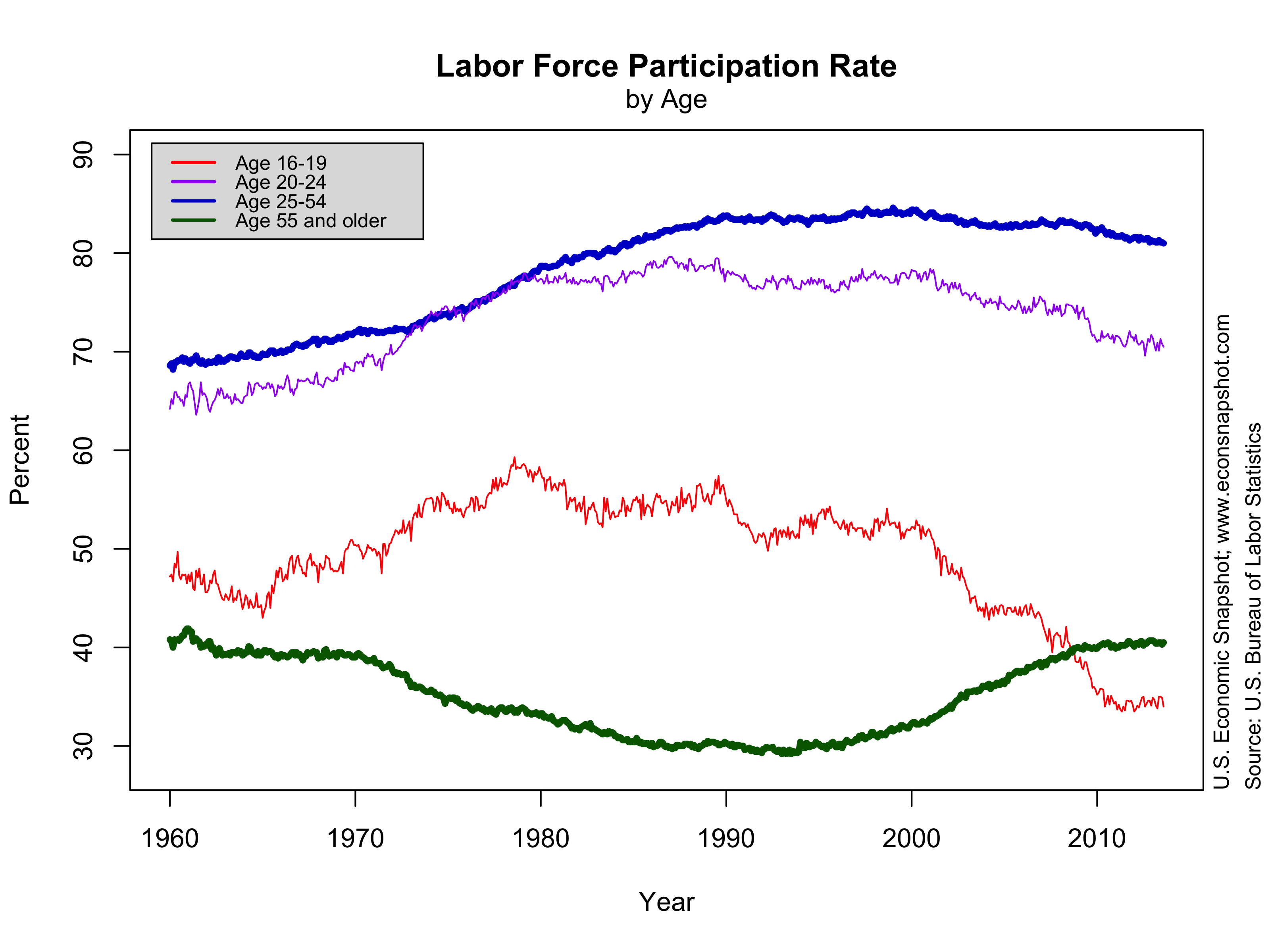

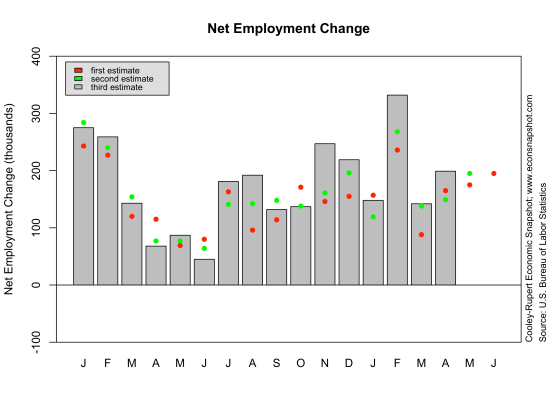

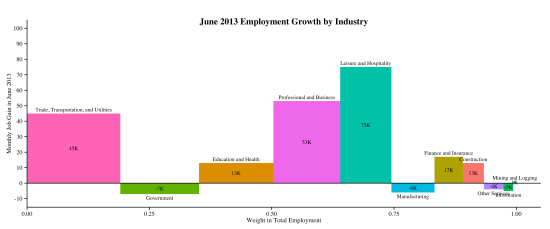

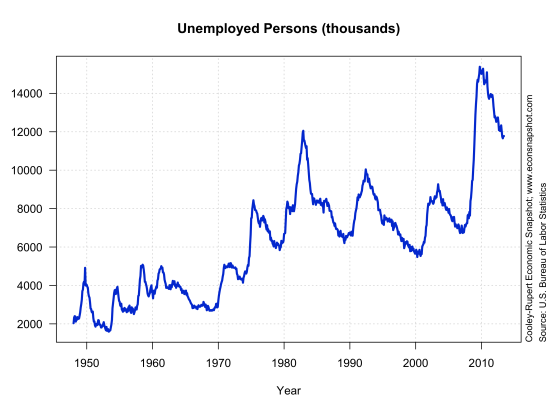

The employment report issued by the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Friday revealed an increase in total non-farm employment of 175,000, close to the median expectation of 170,000. However, the revisions over March and April showed a net loss of 12,000. In addition, about 25,000 of the employment increase came from temporary help services. While the labor force increased (420,000) the labor force participation rate was little changed at 63.4%, and remains substantially below the level in December of 2007. At 7.6% the unemployment rate crept up slightly and number of unemployed persons essentially unchanged.

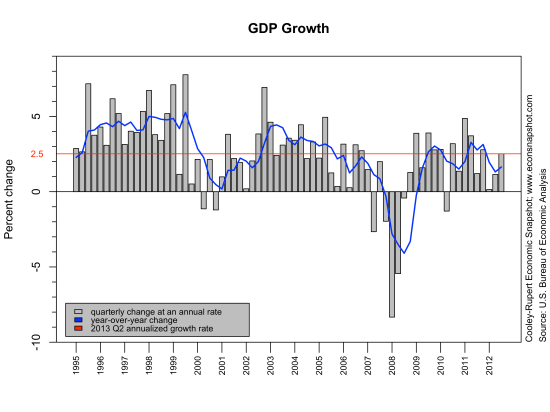

Given this employment report and the fact that GDP continues a slow and steady rise , the policy debate is about when and how fast the Fed will begin to alter its stance on monetary policy. The Fed has repeatedly indicated that its target range for the federal funds rate of 0 to 1/4 percent will be

“…appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.”

This still leaves two uncertainties: (i) when will the unemployment rate fall below 6.5% and (ii) how fast will the Fed increase the federal funds rate after unemployment surpasses the threshold.

The Atlanta Fed’s handy jobs calculator provides some indication on (i). The calculator tells you the average monthly change in payroll employment needed to bring the unemployment rate to a certain threshold in a certain amount of time. Suppose the monthly net employment gain continues to be around 187K (its average over the past year and a half). Then, it would take approximately 18 months to reach the Fed’s unemployment threshold of 6.5%.

As for (ii) what the Fed will do once it reaches this point remains unclear. However, about 20 years ago John Taylor proposed a “rule” that would provide more clarity, i.e., a rule the Fed should (or has been following) follow rather than discretion. The Taylor Rule has become the standard tool that financial market participants look to for guidance about the path of interest rates. The Taylor rule is a sort-of guide to how the fed should ( or does) respond given its targets and the current state of the economy. The idea being that if inflation or output is above some target then the Fed should respond with higher interest rates. How aggressively the Fed should respond (the coefficients of the Taylor rule on deviations from targets) is, of course, debatable. And, in the meantime, there is very little inflationary price pressures, whether one looks at the CPI or PCE or the median CPI.

The current environment is such that the Fed seems to be using a “non-linear” Taylor rule. That is, the Fed will leave the current funds rate alone until the economy reaches the 6.5% rate. It is also unlikely that when the economy does reach that number that the Fed will raise rates in very large steps. It is likely that the Fed will use a “smooth” Taylor rule that be a weighted average of the current rate and the rate implied by the Taylor rule, with more weight on the current rate.

That said, the following graph shows a fairly standard interpretation of the rule. Note that here we use the unemployment rate gap rather than the original output (GDP) gap, since that is what the Fed says it is looking at in the current economic environment. The red line is the effective Fed Funds rate. The blue line is what the Taylor rule prescribes, given a long-term target of 6.5% unemployment and 2% inflation.

The fact that the Fed has emphasized a stance on monetary policy with ‘forward guidance’ is a step toward using a rule. Secondly, that the language of the forward guidance is in terms of the deviation of unemployment from a threshold is a step toward using a Taylor rule. Precisely which rule the Fed will plan to use after the unemployment rate is below 6.5% is debatable.

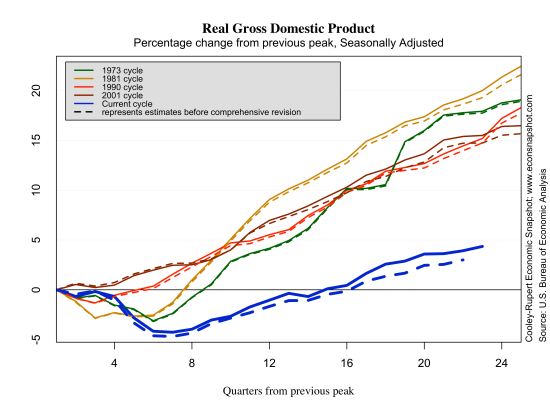

What is quite evident is that it is easy to identify different regimes. The next graph shows the deviations from the Taylor rule. When the green line is below zero it means that the Fed Funds rate was below that implied by the Taylor rule as given in the preceding graph. Of course it may well be that the unemployment rate target was not 6.5% in these earlier periods, the picture below is certainly informative. Moreover, Minneapolis Fed president Kochelakota suggests some benefits if the threshold unemployment rate were 5.5% as he argued here.

That said, there are issues with such an accommodative policy: It is fairly easy to spot the Nixon-Burns years in the 1970’s. The Volcker tightening between 1979 and 1987. The Greenspan years after Volcker were very tightly aligned with the implied Taylor rule until the late 1990’s. In the early 2000’s the Fed maintained a stance of policy with lower interest rates than the Taylor rule suggested.

The near-zero Fed Funds rate has been in existence for some time now while the economy continues to improve–leading to a rate below that specified by the Taylor rule above. While not casting aspersions on leadership…it appears that when the Fed Funds rate has deviated substantially below that implied by the Taylor rule bad things seem to ensue.

All financial market participants know that interest rates have only one way to go – higher. If the Fed were to follow such a rule then changes in the funds rate may occur sooner rather than later. If not, then some clarity about targets and threshholds would probably help given the we are supposed to be operating in a new era of transparency and communication. Markets have been quite volatile in recent weeks and seemingly very sensitive to every signal from the Chairman. Indeed, the Chairman has remarked here that this is an issue that has not gone unnoticed, as the following excerpt shows:

“That said, the Committee is aware that a long period of low interest rates has costs and risks. For example, even as low interest rates have helped create jobs and supported the prices of homes and other assets, savers who rely on interest income from savings accounts or government bonds are receiving very low returns. Another cost, one that we take very seriously, is the possibility that very low interest rates, if maintained too long, could undermine financial stability. For example, investors or portfolio managers dissatisfied with low returns may “reach for yield” by taking on more credit risk, duration risk, or leverage. The Federal Reserve is working to address financial stability concerns through increased monitoring, a more systemic approach to supervising financial firms, and the ongoing implementation of reforms to make the financial system more resilient.”