The Bureau of Economic Analysis announced here that Q2 real GDP increased at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 2.5%, according to the final estimate. Growth in private domestic investment was revised down from 9.9% to 9.2% and government consumption and investment expenditures were revised up from -0.9%to -0.4%. Growth in private consumption was unrevised at 1.8%, but slowed compared to last quarter’s 2.3% pace.

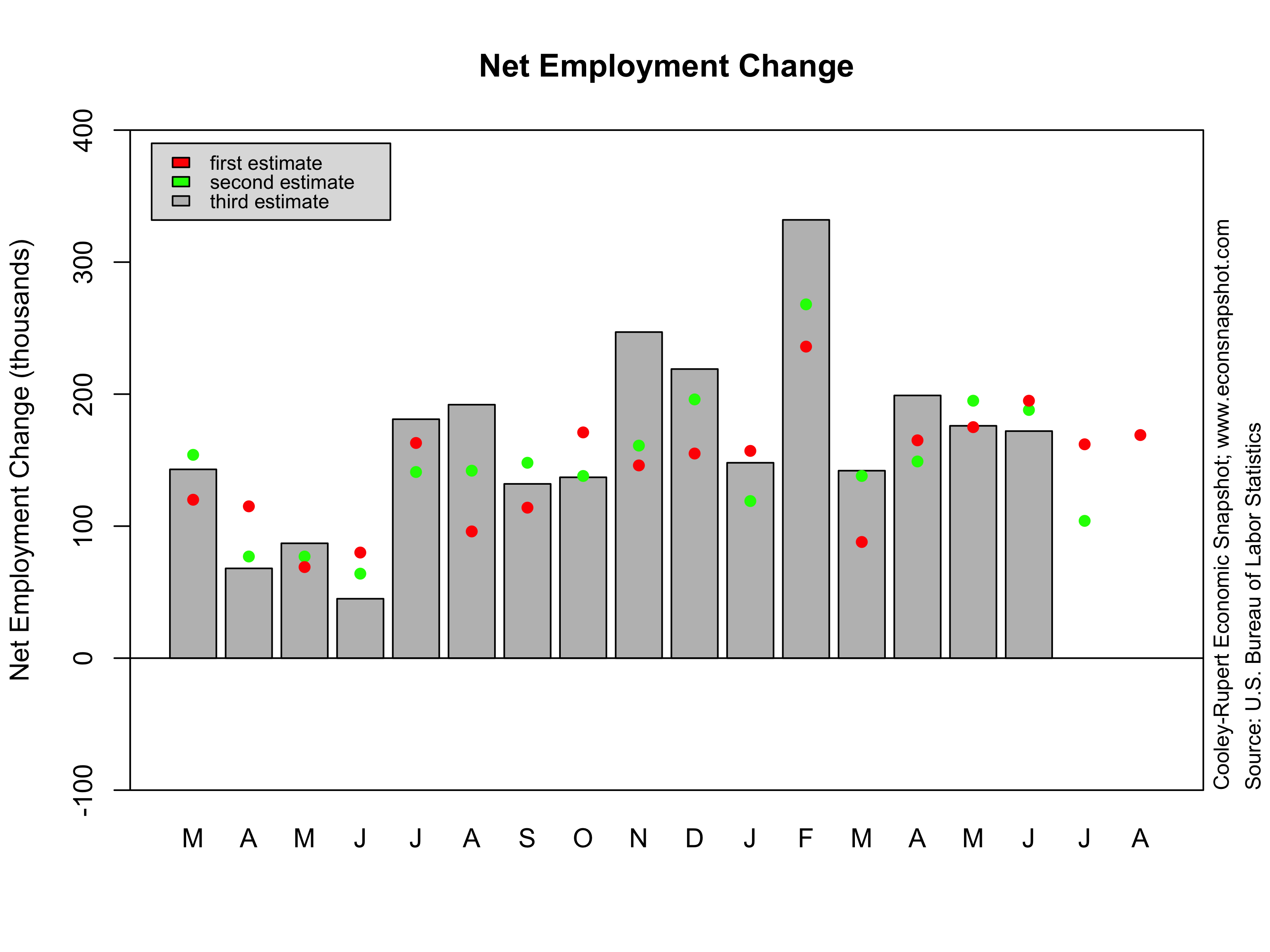

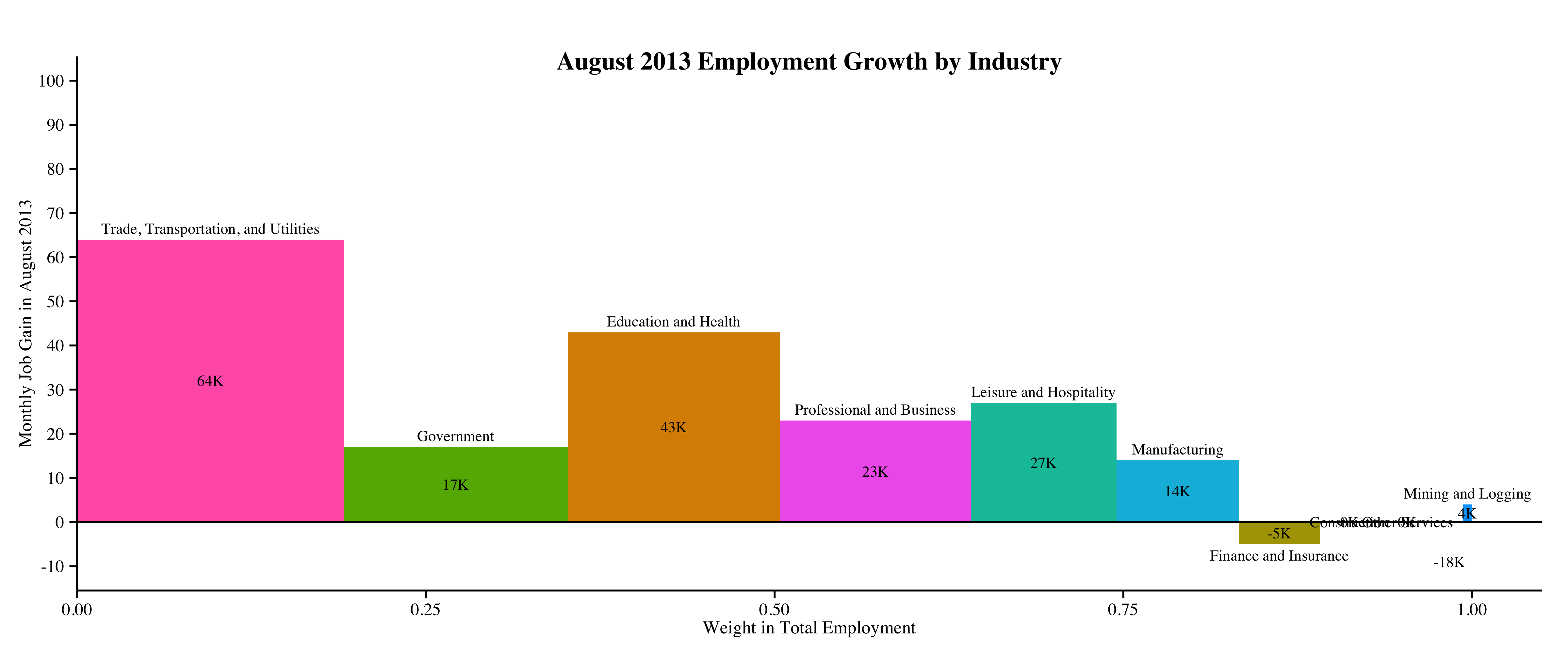

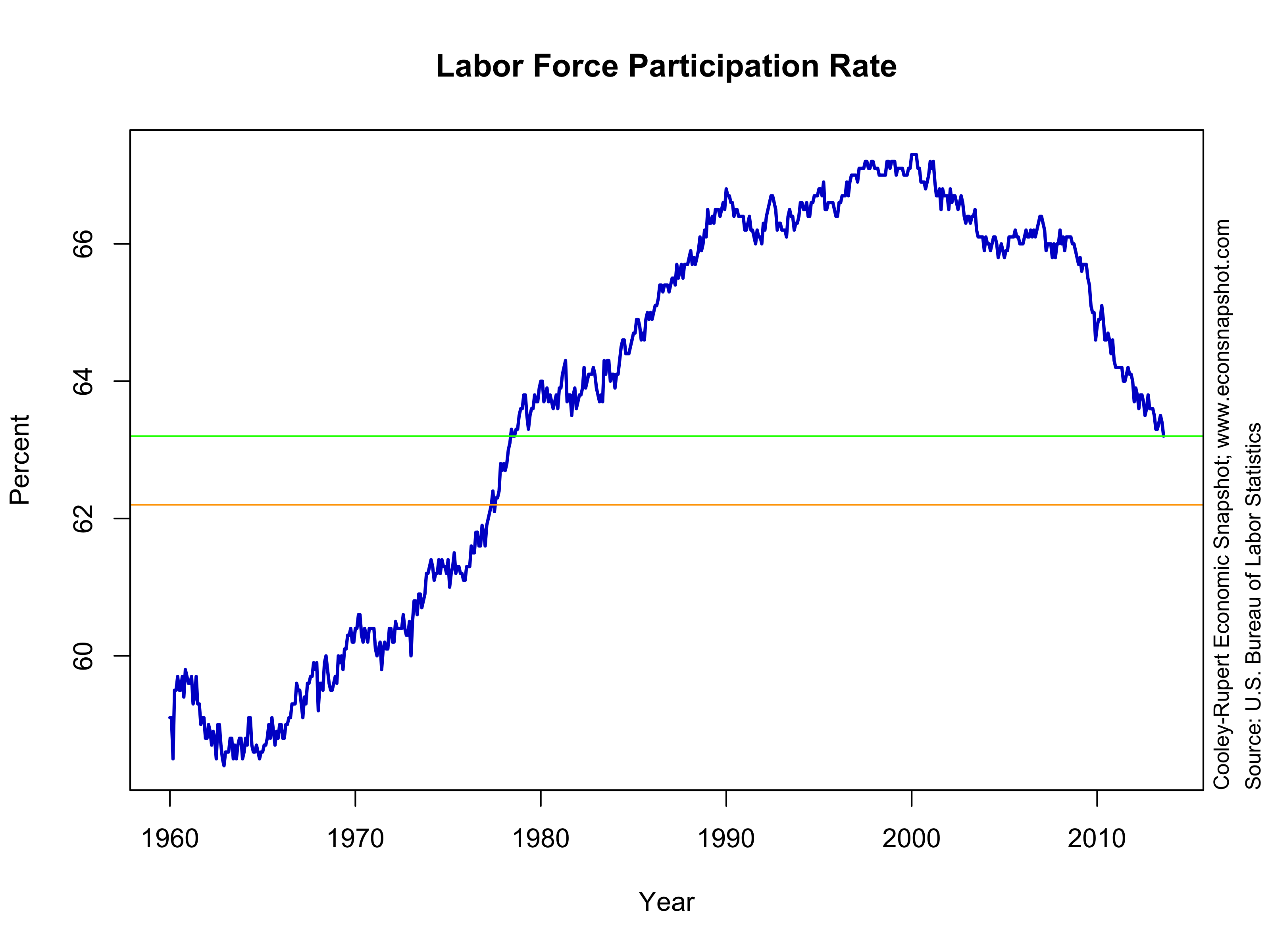

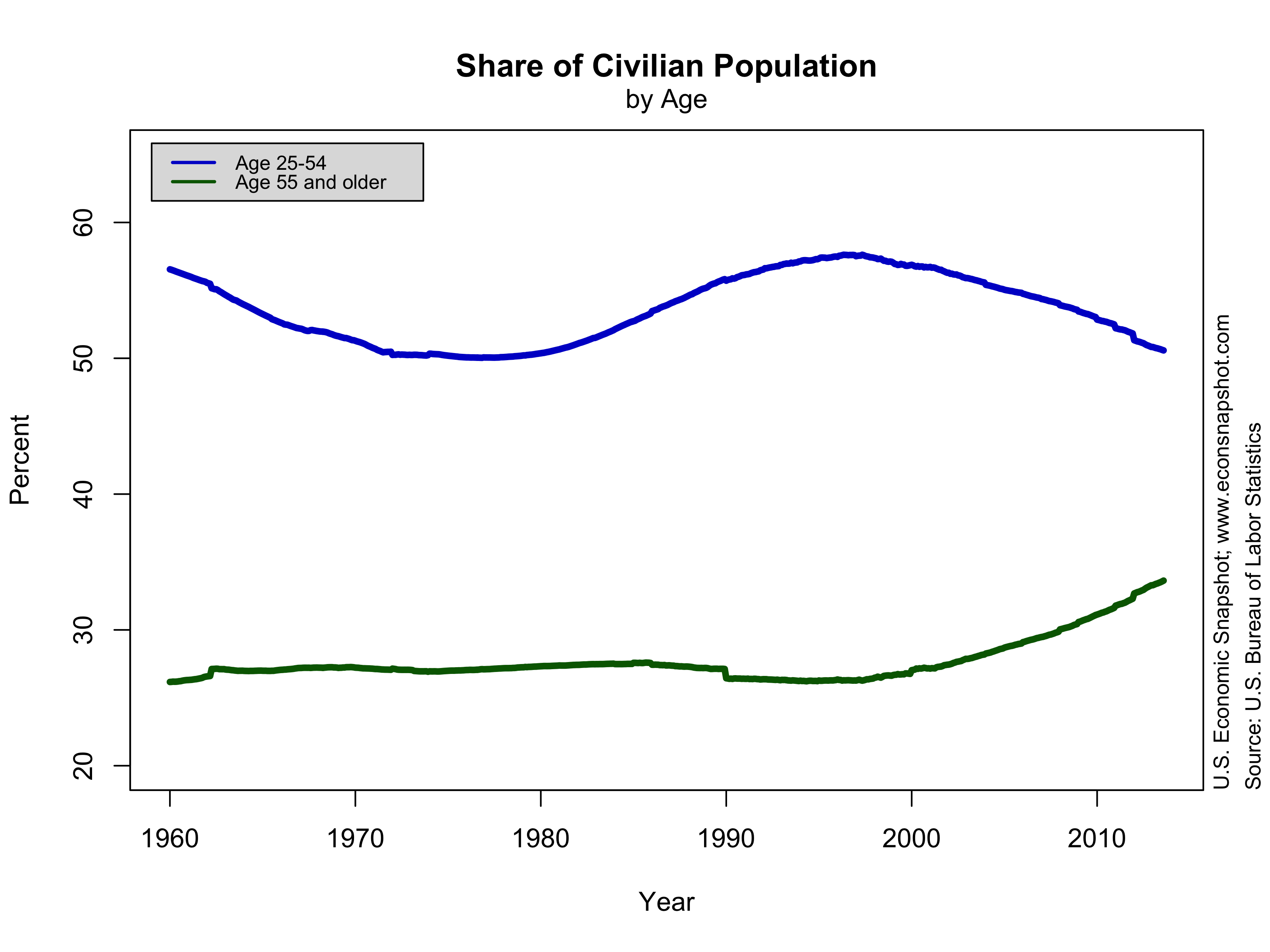

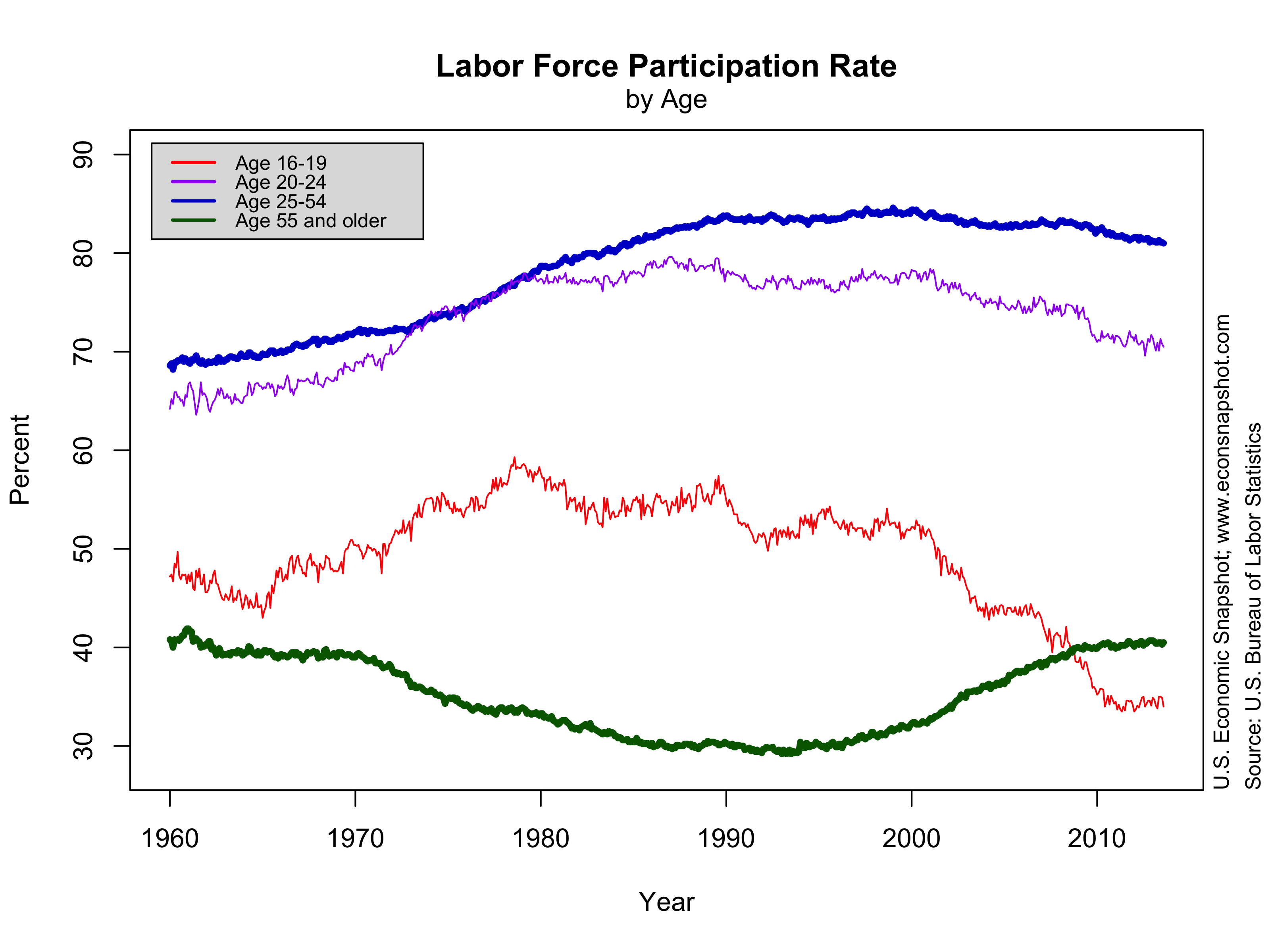

The revised data leaves the broad picture of the economy unchanged. Output, consumption, and income continue to grow at a modest pace. Employment and total hours are steadily growing, albeit slowly. Unemployment is creeping toward 6.5% (the Fed’s stated threshold to possibly, maybe, some chance of, increasing the funds rate) and initial claims dropped 5k, staying near the cycle low.

Not much is new. In fact, not much has really changed in the behavior of the economy since the start of the recovery in June 2009 (NBER’s official date). The graph below shows the series mentioned above, plotted as a percentage of their level in June 2009. From about 2011 onward, the growth rate of these macro ‘fundamentals’ has been pretty stable. GDP has averaged slightly above 2 percent growth (relatively slow compared to past recoveries); consumption has growth been slightly higher at 2.8%. In terms of household income, with the exception of the blip up in late 2012 as a result of the ending of the payroll tax holiday, growth has been steady also.

So, where does that leave the Fed? After the recent non-taper event, Fed officials hailed the move as a sign that the FOMC committee doesn’t follow market expectations, but is rather guided by the data. That data apparently told them that it wasn’t time to start pulling back on large scale asset purchases as a way to begin to unwind the Feds current bloated balance sheet but rather that more stimulus is still needed.

So lets get this straight: the market largely anticipated that the Fed would begin to taper its purchases in September; expectations which the Fed largely dictated with the language of its June FOMC meeting:

Going forward, the economic outcomes that the Committee sees as most likely involve continuing gains in labor markets, supported by moderate growth that picks up over the next several quarters as the near-term restraint from fiscal policy and other headwinds diminishes. We also see inflation moving back toward our 2 percent objective over time. If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year.

The Fed then decided to ‘go against’ expectations, because incoming data suggested stimulus was still needed. Here is what was said by Bernanke after the September meeting [emphasis added]:

The Committee anticipated in June that, subject to certain conditions, it might be appropriate to begin to moderate the pace of purchases later this year, continuing to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, and ending purchases around midyear 2014. However, we also made clear at that time that adjustments to the pace of purchases would depend importantly on the evolution of the economic outlook—in particular, on the receipt of evidence supporting the Committee’s expectation that gains in the labor market will be sustained and that inflation is moving back towards its 2 percent objective over time.

At the meeting concluded earlier today, the sense of the Committee was that the broad contours of the medium-term economic outlook—including economic growth sufficient to support ongoing gains in the labor market, and inflation moving towards its objective—were close to the views it held in June. But in evaluating whether a modest reduction in the pace of asset purchases would be appropriate at this meeting, however, the Committee concluded that the economic data do not yet provide sufficient confirmation of its baseline outlook to warrant such a reduction.

As noted above, there has been almost no change in the rate of improvement in the macro data since 2011. So what exactly did change between the June and September meeting that caused the Fed to alter its stance? From the St. Louis Fed:

“The main macroeconomic surprise in the U.S. since September 2012 has been a lower rate of inflation,” [St. Louis Fed President, Jim] Bullard said. He added that near-term inflation expectations measured from the TIPS market suggested little inflation pressure before the recent FOMC meeting.

“While I expect inflation to rise during the coming quarters, I want to see evidence of such an increase before endorsing less accommodative policy action by the FOMC,” Bullard said.

In June, they believed that ‘inflation [will move] back toward our 2 percent objective over time”. Now in September, they still believe inflation will continue to rise, but that since it remains below 2 percent, QE will continue.

With the addition of inflation to the threshold calculus it seems that “forward guidance” should no longer be in the vocabulary of Fed policy–as it now has little meaning to market participants beyond a dual mandate objective.

A good thought spoiled. Or was it a good thought at all? Sure, it was with the best intentions…but how could it be implemented? And where does the Taylor rule fit in to the forward guidance policy…a rule that calls for an increase in the funds rate?

Evidently, (of course) forward guidance it is not a rule at all, nor was it intended to be.

Where does this leave us? Well, the economy is continuing to recover. Unemployment is coming down, inflation is moving slowly toward the FOMC target of 2%. Not much different from a year ago…not much should be different in October or December. Will policy decisions remain the same? Well, we

”will closely monitor incoming information on economic and financial developments in coming months…’

Remember: you can always find the full ‘Snapshot’ of the US Economy here and on the main page.