by Zach Bethune, Thomas Cooley and Peter Rupert

The labor market added 252,000 jobs in December according to the Employment Situation released today. In addition, there were substantial positive revisions to last two months: 243k to 261k in October and 321k to 353k in November.

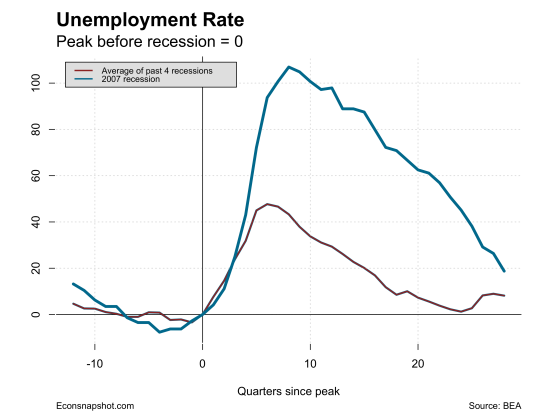

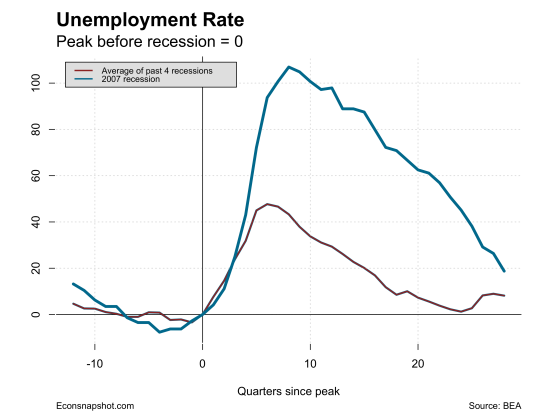

The unemployment rate declined to 5.6%, which marks the lowest it has been since mid 2008. While the number of unemployed workers hasn’t fallen to its pre-recession level, the remaining ‘slack’ left in the labor market is largely due to the longer-term unemployed or those with jobs but who are underutilized, like the part-time workers for economic reasons. The story in terms of how (and in which dimensions) the labor market is recovering remains the same: slow but continued progress after a historically deep recession.

Our usual goal in these posts is to describe where the US is in its now 7-year recovery from the recent recession. However, we ask a different question in this post (one that has been the central focus of many economists since the crisis started): why was the downturn in the labor market so deep?

The Labor Market Downturn

Compared to past recessions, the increase in unemployment during the Great Recession was the worst since the Great Depression. The unemployment rate more than doubled from mid 2007 to late 2009. Even compared to recent recessions, this crisis was particularly severe. What factors led to such a severe recession? In my job market paper, “Consumer Credit, Unemployment, and Aggregate Labor Market Dynamics”, I study the role of households’ ability to access and use consumer credit when they become unemployed and ask if this relationship, at the household level, can help us explain the depth of the recent recession.

The Role of Consumer Credit

The Great Recession was unique in many respects, but a feature that continually stands out has been the response of household debt and borrowing. The credit boom of the late 1990s led many households to increase their reliance on debt to finance consumption and investment. The ratio of debt-to-income increased from around 0.6 in the 1980s to nearly 1.2 at the peak of the boom in 2007. During the crash, both debt and borrowing fell at rates never seen before as the unemployment rate doubled. Debt-to-income currently stands around 0.95.

Not only was the pattern in unemployment and borrowing similar in the aggregate, we also see them linked if we look across regions of the US. For instance, counties that had the largest increase, and subsequent fall, in borrowing during the Great Recession also tended to be the counties that experienced the largest declines in employment or increases in unemployment (see an excellent non-technical summary of this work here). These facts have led to a new emphasis on research into how problems in household financial markets might exacerbate recessions.

One area of household debt that was a strong predictor of the response of unemployment was borrowing on consumer credit lines, mostly comprised of credit cards(Mian and Sufi, 2009). The fall in consumer credit borrowing between 2007 and 2009 was nearly twice as large as in the previous 4 recessions.

Not only were households borrowing less, it was also more difficult to access the consumer credit market. Evidence from the Federal Reserve Board’s Senior Loan Officer’s Survey suggests that lenders were tightening credit card standards and also decreasing limits on outstanding accounts. Consumer credit became more difficult to access during the Great Recession at the same time that the labor market was deteriorating.

This leads to the question of what was happening at the household level between a consumer’s access to credit and their labor market status. Evidence from the 2007-2009 Panel Survey of Consumer Finances suggests that not only was credit being tightened for all consumers over this time period, but that it was being tightened more strongly for consumers that lost their jobs. These households applied for credit more frequently and were denied at a higher rate. The difference in the rate of denials was driven by denials that were employment and income related, being told by lenders that their income was too low. In the end, the rate of monthly borrowing fell 60% more for an average consumer that lost their job than an average consumer that maintained employment. Put simply, a job loss over the Great Recession corresponded to a significant reduction in a household’s ability to borrow on consumer credit.

Accounting for this relationship in a macroeconomic model leads to recessions that are around 70% deeper than what a standard model would predict. A shock to the economy, say a fall in productivity or house prices, gets amplified if the unemployed face tighter credit constraints. As the unemployment rate increases, a higher fraction of households are credit constrained, borrowing falls, and subsequently the demand for firms’ products. The decrease in ‘aggregate demand’ lowers firms’ demand for labor which induces more unemployment. This cycle repeats itself, causing the recession to become deeper.

Conclusions

The evidence above highlights two aspects of why the fall in household borrowing between 2007 and 2009 corresponded closely with the increase in unemployment. First, the complementarities between the household credit market and the labor market run down to the household level. It became more difficult to borrow precisely for households that demanded it the most, the unemployed. Second, this relationship affected the incentives for firms to hire, which exacerbated the initial causes of the recession. Accounting for the relationship between borrowing and unemployment at the household level is important in understanding the trends we see aggregate data.

Sources

Bethune, Zachary (2014), “Consumer Credit, Unemployment, and Aggregate Labor Market Dynamics” in mimeo.

Mian, Atif and Amir Sufi (2010), “Household Leverage and the Recession of 2007 to 2009” IMF Economic Review, Palgrave Macmillan, vol. 58(1), pages 74-117, August.